- Ode to the flâneur

|

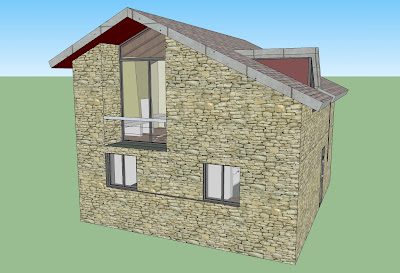

| click image to enlarge |

Just passing through

With pressure of seemingly ever increasing population numbers in urban areas and the resultant expansion, the distances required to travel are pushing moving around to levels where they are too dominant a proportion of time spent. (Although global population growth could be stabilising - see Pearce F, Peoplequake: Mass Migration, Ageing Nations and the Coming Population Crash, 2010, Bantam)

We are experiencing many cases of ‘urban sprawl’ type expansion of cities which brings issues of lack of access to basic facilities, as they are often not ‘officially’ recognised areas, as well as the travel issues. Sometimes these areas can function quite well from a socio-economic despite poor physical conditions, so should not be written off as areas just for clearance and re-development; whatever they are, they are people’s homes.

Enforced commuting of large numbers of people over large distances is unsustainable, both in terms of people’s quality of life and in level of transport required to support that volume of daily movement. So there is a need to find ways to reduce the amount of enforced travel; to allow a higher proportion of travel by choice (within a reduced overall level) and for it to once again become part of a pleasurable pastime or experience, be it by car, bus, train, bicycle or on foot. [For the ‘on foot’ consideration - in many ways the most important - see additional reference texts for flâneur and psychogeography, below.]

Whilst wandering and promenading are laudable and worthwhile pursuits, here we do not seek directly the notion of the flâneur, but that of being more conscious of experiencing a shared sense of place along the street as a richly layered active space, rather then merely being a route; the traditional difference between a ‘street’ and a ‘road’.

Out and about

We increasingly no longer relate to the street as a space in itself, but more just as a means to get to a specific function, which actually diffracts our notion of a 'street'. Therefore, the starting point for the design of the helical street is to explore how to re-link the disparate elements, aspects and activities that constitute the street as a dynamic place - integrated yet layered; the mandate being to re-establish the core aspects of the street, which will cultivate better awareness of others around us and address notions of isolation. This sense of isolation leads to a reduced sense of connection with places we use and the people that constitute them, that itself leads to a reduced sense of community.

Even though how we live is shifting, and the traditional idea of community is perhaps less common - where most people in an area work and live there - it is still important that the evolving notion of community is cultivated. We increasingly have a much wider movement ‘net’ with nodes further apart, in that we live, work and socialise in many different areas, so there is a rich nexus of overlaid social ‘nets’ that constitute places. Merely because people in a place have not come from just that locale, does not invalidate it as a cohesive arena of activity, it just means we need to acknowledge that evolved sensed of community.

If we are more aware of those around us and we operate from a sense of awareness and respect, we can embrace a new sense of camaraderie without necessarily needing to know, or even recognise personally, most of the people around us. This issue relates to the current reduced sense of the ‘civic’, in parallel with the above mentioned isolation, but also from the perspective of reduced governmental investment in civic infrastructure, as some regions, particularly the UK and already to a greater extent the US, become more commercially operated. Where solely in response to unsustainable urban growth, wider nets should be countered; where out of choice or genuinely diverse neighbourhoods, it is more acceptable as a general trend of how society is evolving.

Spineless

The traditional high street serves as the ‘spine’ of a neighbourhood and, ideally, is ‘mixed-use’, with residential flats over a commercial workshop, studio or office, with retail at ground floor. Although many high streets have much empty space above the ground floor, this is more often to do with concerns such as access and loss of retail width - which is easily resolvable - rather than accumulated commercial reasons. (Many high street situations would not see a reduction in commercial value for a slightly reduced retail width to allow residential access from the front, rather than the often unpalatable service area at the rear.) It is the holistic re-establishment of how a street functions that the design seeks.

Each ‘neighbourhood’ of the helical street has a good mix of functions to ensure they can evolve sustainably. Furthermore, different areas can be more focussed to provide a greater diversity of places overall: quiet, busy; cultural, retail; working, residential, which gives a richness and variety of encountering different people and neighbourhoods as when walking through our best cities.

That sections can be chosen as certain distinct types of area with more direct access means overall the helical street tower can support a longer high street equivalent than would be the case at ground level, and still be within walking distance (including use of lifts).

Whilst a key difference is that whilst it is not a through route per se, this is mitigated by the more focussed mix of amenities. Although it could in one sense reduce the breadth of range of people types for chance encounters in any particular place - as people will tend to choose their preferred section and not pass along the whole of the street - this does not reduce the experience of encountering people generally; this will be the same or better, with the more vibrant neighbourhoods encouraging promenading. This is further helped by there being no vehicular traffic (deliveries with the lifts), although cars are not necessarily a problem and can be a benefit in a normal street situation, but are often managed badly. Overall, the three dimensional movement makes for a more cohesive destination.

On the street

The ‘vertical street’ is formed by taking the pavement of a typical street and its adjacent buildings and spiralling them up and around to form a (partially open-sided) tower with the pavement as a helical ramp - the building fabric forming the outer shell of the tower - where pedestrians can walk at their leisure. A central atrium space with lifts (shown as three pairs of circular lift shafts on the model) allows direct access to different ‘neighbourhoods’, analogous to bus stops along a high street.

The vertical street allows visual connection across the central atrium space and along the curve of the street, which creates a sense of place as it ‘contains’ a rolling space as people progress around. This counters the effect of overly straight streets that allow the eye to wander to infinity and thus people to become more psychologically removed. At intermittent intervals up the ‘street’, there are central platforms forming areas of respite within the central space, akin to parks and squares stumbled upon, adding the prospect of surprise to our meanderings.

Inevitably there will some comparisons between the helical street and the ‘streets-in-the-air’, which were part of many housing estate projects built, often in outlying areas, during the 1960s and into the 1970s, particularly in the UK. This isolated people as it was based on divorcing different types of routes so lost ‘critical mass’ and lacked the density of numbers of people, but the helical street has all movement still together and the concentration of functions achieves a higher intensity of use.

Another related phenomenon is shopping malls. The helical street takes some of the better aspects of shopping malls - in principle an active destination - but without the unsustainable weaknesses, such as being internalised and mostly only retail; at best not linking out to the broader community, and at worse, actually taking life away from the main high street (whether adjacent or not). Although, there are street based examples of the ‘out-of-town’ shopping malls in city centres: Liverpool One, which stitches together the main centre with the waterfront, although the highway in between was inexplicably left out of the scheme. Out-of-town ‘works’ (for itself – not surrounding neighbourhood) only until the next one is built nearby which is ‘shinier’. Therefore even developers building malls that are more street based with a broader mix of uses would see a better overall return from this more sustainable version, as long as they retain a longer term interest (which they should) rather than just sell off post-construction.

The modular nature of the helical street could support some ‘chain’ type shops (‘nationals’/ ‘multiples’) in multi-width units, but the small unit layout and step would tend to act as a natural limiter. A few chain type shops can act as a draw, but this needs to be balanced with independent shops and mixed together. So the modular unit being well suited to smaller, typically more independent, shops and activities will be the natural tendency, as well as being part of the management criteria.

Babel

Towers, in principle, could be an appropriate typology to help address some current issues, such as urban sprawl. However, ‘skyscrapers’ have not really evolved as a typology since their inception; essentially accommodation in the tower just ‘fills up’ a structure primarily conceived to be tall. They may have developed almost unrecognisably, but this is really little more than a multiplication: being taller with faster lifts, rather than evolving as such.

One of the key problems with most towers is that of relating to human- and street scale at the base: a lobby in scale with the tower is often out of scale with the human, which then often presents a harsh and unwelcoming environment; the notion of an imposing entrance being impressive having been, thankfully, superceded with a general move towards human centred development, although such anachronisms do persist in too many places. (see Out-of-Scale: Rapid Development in China, Urban Design Journal, issue 99, Summer 2006, Nuffield Press, London)

The second aspect is that of scale and integration of massing. Typically, good high streets would be constituted by four to six storey buildings as a general principle, so a tower touching directly down at ground level would again present an inappropriate scale. Towers emerging from a more human scale podium base of four to six storeys gives a much smoother transition, so integrates better to the adjacent street.

The proposed design may initially appear like a conventional tower. However, as discussed above, it has a fundamentally different access due to the helical ramp, and lifts, which means the way it is used and experienced sets it apart from conventional towers. This is further augmented because the structure is a relatively closely spaced vertical frame between each stack of accommodation spaces, so allows some sections or individual elements to be removed, vertically or horizontally, to form spaces for parks, terraces, light and views out. This configuration can achieve a series of cascading spaces either for an internal space, be it a flat, studio or shop, or as an outside space, such as a park or square. (Ken Yeang has been developing such ideas since the last quarter of the previous century.)

The structure ensures that the whole can evolve sustainably at a variety of scales over time: the whole tower could be replaced in phases, or over a longer period of time in smaller stages. Also individual units can be removed, at construction or later; spaces can be plugged; floors can be joined up or knocked through - horizontally or vertically. Such flexibility and array of spaces can be explored to develop an experience of the tower itself, rather than being merely a function of its height.

Light, air and orientation will be important and are integrated, partially through the openings already mentioned, although these are more for spatial and functional reasons, but primarily through three vertical slots: one double unit width to the North, and two single unit width slots to the South East and South West, all being adjacent to lift lobby platforms so providing views out and clear orientation for people (an issue with circular constructions, particularly when use as navigating landmarks around the city). Detailed light and wind studies will suggest further refinements towards a good overall environment. Lifts are placed at thirds of a revolution around the street, with a full circumference of 150 metres, providing vertical access every 50 metres, in line with good urban design principles for rhythm of cross streets along any conventional high street.

The actual configuration of the street proportion is based on a three storey high building (10 metres) and a 9.5 metre wide street, giving a roughly 1:1 proportion of space, (in section through the street). The street itself will feel wider due to the open inner side, so psychologically push more towards a 1:1.5 wide proportion, both of which are considered decent proportions for high streets. The geometry derives from a series of interconnected variables that need to be finely balanced so that steepness of slope, distance around the circumference, view across the central atrium and height of buildings, achieve a good overall equilibrium.

‘It is the pervading law of all things organic, and inorganic; of all things physical and metaphysical; of all things human and all things super-human; of all true manifestations of the head, of the heart, of the soul; that the life is recognizable in its expression, that form ever follows function.’

– Louis Sullivan, 1865 – 1924

Related references

(drawn from Wiki)

Flâneur

The term flâneur comes from the French masculine noun ‘flâneur’ - which has the basic meanings of ‘stroller’, ‘lounger’, ‘saunterer’, or ‘loafer’. Charles Baudelaire developed a derived meaning of ‘flâneur’ (originally from the verb flâner - ‘to stroll’) - that of ‘a person who walks the city in order to experience it.’

While Baudelaire characterised the flâneur as a ‘gentleman stroller of city streets’, he saw the flâneur as having a key role in understanding, participating in and portraying the city. The idea of the flâneur has accumulated significant meaning as a referent for understanding urban phenomena and modernity. A flâneur thus played a double role in city life and in theory, that combines sociological, anthropological, literary and historical notions of the relationship between the individual and the greater populace.

David Harvey asserts that ‘Baudelaire would be torn the rest of his life between the stances of the dandy and flâneur, a disengaged and cynical voyeur on the one hand, and man of the people who enters into the life of his subjects with passion on the other’. (Paris: Capital of Modernity 14).

[The dandy aspect of flâneur achieves new relevance with shopping emerging as a leisure activity and increasing celebrity reverence as an aspiration, which twin pursuits continue to supplant both faith and ritual. These two notions being a ‘hard-wired’ part of our social cohesion, but have been so dominated by religion we treat them as synonymous with it. But as religion wanes, a vacuum is left, which shopping and celebrity reverence rush into to fulfil these notions of faith (hope) and ritual (celebration) - Ingenu]

The observer-participant dialectic is evidenced in part by the dandy culture. Highly self-aware, and to a certain degree flamboyant and theatrical, dandies of the mid-nineteenth century created scenes through outrageous acts like walking turtles on leashes down the streets of Paris. Such acts exemplify a flâneur's active participation in and fascination with street life, while displaying a critical attitude towards the uniformity, speed and anonymity of modern life in the city.

The concept of the flâneur is important in academic discussions of the phenomenon of modernity. While Baudelaire's aesthetic and critical visions helped open up the modern city as a space for investigation, theorists, such as Georg Simmel, began to codify the urban experience in more sociological and psychological terms. In his essay The Metropolis and Mental Life, Simmel theorises that the complexities of the modern city create new social bonds and new attitudes towards others. The modern city was transforming humans, giving them a new relationship to time and space, inculcating in them a ‘blasé attitude’, and altering fundamental notions of freedom and being.

- ‘There is no English equivalent for the French word flâneur, just as there is no Anglo-Saxon counterpart of that essentially Gallic individual, the deliberately aimless pedestrian, unencumbered by any obligation or sense of urgency, who, being French and therefore frugal, wastes nothing, including his time which he spends with the leisurely discrimination of a gourmet, savouring the multiple flavours of his city.’ - Cornelia Otis Skinner, Elegant Wits and Grand Horizontals, 1962, Houghton Mifflin, New York

- ‘The photographer is an armed version of the solitary walker reconnoitering, stalking, cruising the urban inferno, the voyeuristic stroller who discovers the city as a landscape of voluptuous extremes. Adept of the joys of watching, connoisseur of empathy, the flâneur finds the world “picturesque”’ - Susan Sontag, 1977 essay, On Photography

Psychogeography

Psychogeography was defined in 1955 by Guy Debord as ‘the study of the precise laws and specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behavior of individuals.’ Another definition is ‘a whole toy box full of playful, inventive strategies for exploring cities... just about anything that takes pedestrians off their predictable paths and jolts them into a new awareness of the urban landscape.’

In 1956, the Lettrists joined the International Movement for an Imaginist Bauhaus to set a proper definition for the idea announced by Gil J. Wolman, Unitary Urbanism – ‘the synthesis of art and technology that we call for must be constructed according to certain new values of life, values which now need to be distinguished and disseminated.’ It demanded the rejection of both functional, Euclidean values in architecture, as well as the separation between art and its surroundings. The execution of unitary urbanism corrupts one's ability to identify where ‘function’ ends and ‘play’ (the ‘ludic’) begins, resulting in what the Lettrist International and Situationist International believed to be a utopia where one was constantly exploring, free of determining factors.